Hochul Math: The governor’s power grab to rewrite climate law

Let me explain the painfully nerdy, incredibly important methane math problem that roiled New York’s budget process this week.

It’s been a hell of a week in Albany. The state budget is late, and the fights are ferocious.

Even if you were paying attention, you might have missed this one: While the bail reform battle was occupying the spotlight, and with the budget fight playing out mostly behind closed doors, Gov. Kathy Hochul tried to push through a major change to the way New York does climate math.

Here’s what we know: Armed with outsized budget-season power, and with the support of the natural gas industry, Hochul threw her weight behind an obscure bill introduced late in the budget session by Senator Kevin Parker and Assemblymember Didi Barrett, who chair the energy committees in their respective houses. The bill, S6030, proposed a couple of sweeping changes to the method New York uses to count its greenhouse gas emissions.

If adopted, S6030 would cast New York’s newly-adopted climate plan into limbo by changing the figures that provide the foundation for its 400-plus pages of policy recommendations. It would also have brought New York’s accounting in line with the way methane is counted by most other states and the federal government — a method climate scientists say is outdated, and that underestimates the outsized impact that natural gas leaks and other major methane sources have on climate change.

Facing swift backlash from climate advocates, their allies in the state legislature, and appointed members of the Climate Action Council that developed the plan, the Hochul administration moved to defend the bill in public, claiming that it would lower the cost of climate action to ordinary New York households — and, in the process, stirring up fresh alarm about the costs of a state cap-and-invest program. An unnamed Hochul official told Politico that a cap-and-invest program with New York’s tougher math would raise the price of a gallon of gasoline by 63 cents, and that 100-year math would raise it by 39 cents. CAC co-chairs Basil Seggos and Doreen Harris, who head up the state Department of Environmental Conservation and NYSERDA respectively, appeared on Capital Tonight to defend the accounting move, sparking howls of outrage from some of the rank-and-file members of the CAC.

Today, with news outlets increasingly tuning in to cover the issue, and internationally-known climate experts jumping into the fray, Hochul backed off, telling Albany reporters that she was dropping the push to revise the state’s methane accounting.

No harm done, it seems — except, perhaps to Seggos’ reputation as someone with the spine to stand up to governors, and to public trust in New York’s climate policymaking, which is arguably already pretty shaky. For now, New York will keep its tougher climate accounting.

Why the push to change the math?

New York’s climate law, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, was adopted in 2019. The use of a 20-year methane accounting method is written into the law. It’s been a few years since it passed, but little of the law has been put into concrete action.

This year may be different. The state’s climate plan, required by the CLCPA, is finally finished as of January. Several important bills that would begin to put teeth in the CLCPA are currently on the table in state budget negotiations.

The legislature might deliver some big-ticket climate law this year. The All Electric Building Act would start the clock on requiring new buildings to have high-efficiency electric heat. The Build Public Renewables Act, or some version of it, would enable the New York Power Authority to build publicly-owned renewable power. NY HEAT would align state utility law with climate goals, and task the Public Service Commission with planning for the transition away from natural gas. The Climate Change Superfund Act would create a new fund for paying for disaster damages, funded by fees charged to large fossil fuel companies. And if Hochul and the legislature come to a budget deal on a cap-and-invest program, large polluters will pay a fee to produce greenhouse gas emissions in New York, with funds raised to be put toward decarbonization projects and rebates to New York households.

The closer the legislature has come to passing substantial climate bills, the fiercer the pushback from the fossil fuel industry has gotten. Assemblymember Emily Gallagher, cosponsor of the All Electric Building Act, pointed a finger at National Grid as a powerful force behind the latest dustup.

Whether or not the governor was acting on behalf of fossil fuel interests, raising the issue during zero-hour budget negotiations was an aggressive move.

“This is the moment when the governor has the most power that she has in the whole year,” Gallagher told climate advocates on a Zoom call Monday night. “It’s getting into a tricky, scary situation, because the budget was already due by April 1.”

What would happen if the Parker/Barrett bill passed?

The most obvious impact of changing the state’s methane accounting method would be to turn down some of the pressure on cutting emissions from natural gas.

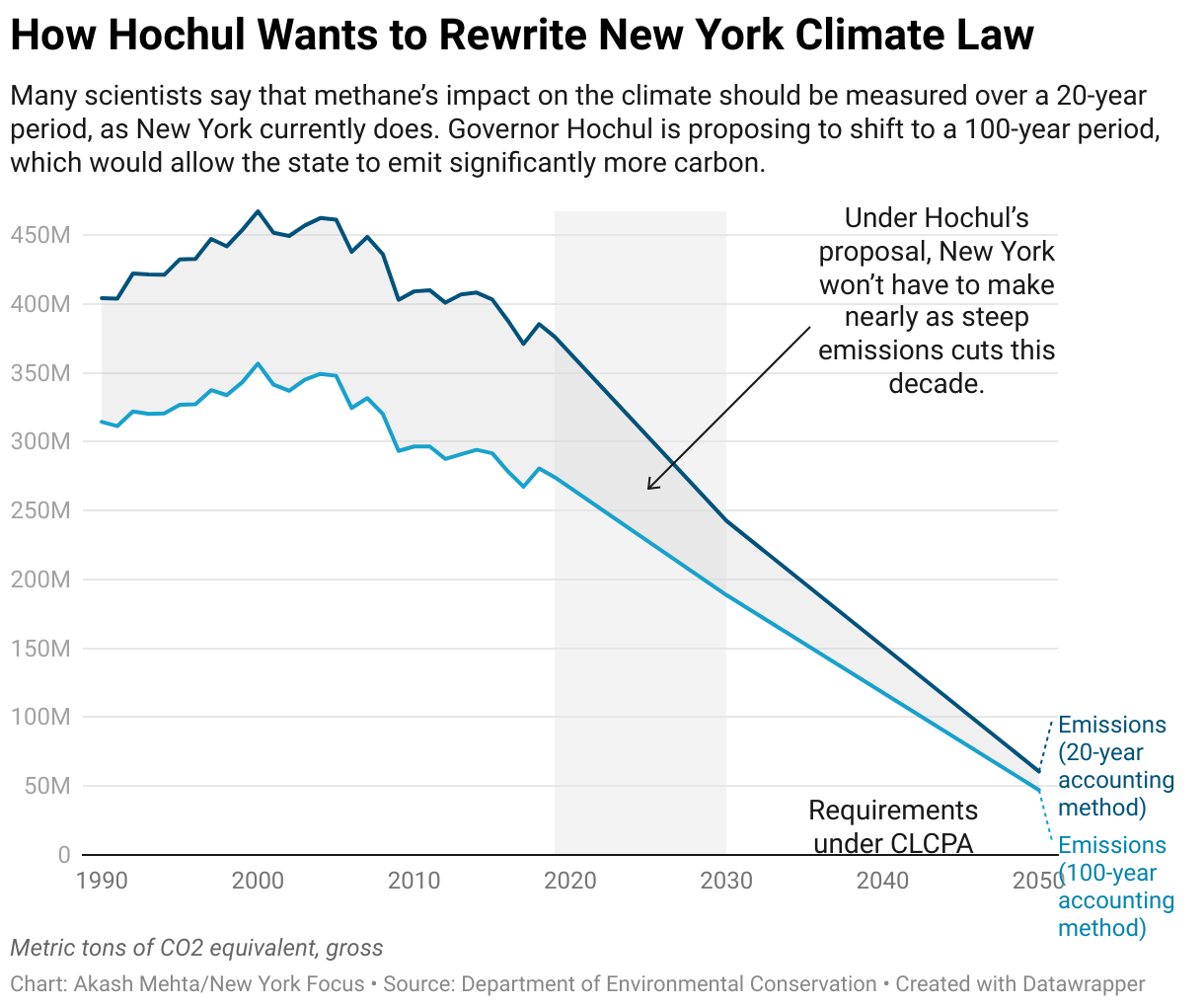

In a story that explains how Hochul’s effort to change state climate accounting threw a “grenade” into the budget process, NY Focus reports that adopting 100-year methane math would mean that the state only has to cut 86 megatons’ worth of carbon emissions over the next decade, not 134.

Although the slowdown in climate action that Hochul Math would cause is alarming on its face, it’s not quite as bad as it looks. The new math also shifts the definition of what counts as a “ton” of emissions. As local climate advocate Sean Dague pointed out on Twitter, comparing 86 megatons to 134 is a bit like conflating Canadian with US dollars: 86 tons of “Hochul Math” cuts actually represent a greater reduction in emissions than 86 tons of “20-Year Math” cuts.

If that’s too confusing, maybe it helps to look at it like this: Under the state’s current, more rigorous method, the state will have to get rid of about 36 percent of its greenhouse gas emissions between 2019 and 2030. Under looser Hochul Math, the goal would be to cut those emissions by about 31 percent over that same time period.

Adopting Hochul Math would also lead to an increase in emissions from burning “renewable natural gas” derived from farms and waste, in addition to other biofuels. New York currently counts those emissions toward the total, but the Parker/Barrett bill would redefine biofuels as zero-emissions.

The downplaying of methane emissions would also lead to a shift in priorities. Under the state’s current accounting, New York State’s number one emissions problem is coming from the buildings sector. About a third of the state’s emissions come from burning fuel to heat and cool buildings, according to NYSERDA figures calculated with the 20-year method. Transportation emissions are a close second.

Reducing the weight of methane in those figures through accounting sleight-of-hand doesn’t change physics: Leaks in the natural gas pipelines that feed millions of New York homes will still be a massive climate problem over the next few decades. But relaxing the timeframe would make transportation, where a greater share of emissions are from carbon dioxide, look like a bigger climate problem than home heat.

Why can’t New York count both ways?

Short answer: We can. Nothing is stopping the state from using 20-year accounting to track progress toward state targets, and also 100-year accounting to crunch numbers on projects that are eligible for federal Inflation Reduction Act clean-energy incentives or other federal funding.

“There is nothing in the IRA that precludes New York from setting its own timescale standard, just like California has set its own standards for automobile emissions,” a group of climate scientists write in an April 5 open letter to Hochul and state legislators.

Supporters of the Parker/Barrett bill claim that New York needs to adopt 100-year methane accounting in order for state projects to qualify for IRA funding.

“My office reached out to Chuck Schumer’s office to fact-check that, and it’s absolutely not true,” Gallagher said. “No matter how you’re evaluating methane, that’s not going to interfere with access to IRA funds.”

What’s so bad about changing the math?

On its face, the shift seems reasonable. Maryland and New York are the only two states that use the more rigorous 20-year method for counting methane impact. The rest of the states, and the federal government, count over a 100-year timespan.

The trouble is that 100-year methane accounting is a relic: a best guess based on outdated science. It’s a holdover from international climate agreements in the 1990s, when scientists did not yet appreciate methane’s outsized impact on climate change, or the vast extent of methane leakage from fossil fuel mining as well as from natural-gas distribution systems.

Climate scientists say that in order to stave off the worst climate futures, deep emissions cuts must be made in the next decade — and although unburned methane decays relatively quickly, its potency in the short term is far greater than that of carbon dioxide. In the first seven years after methane is leaked into the atmosphere, it is 109 times more effective at trapping atmospheric heat than carbon dioxide. By about a decade after its release, the gas has mostly decayed into carbon dioxide and water, and lost most of its heat-trapping power. Averaging the front-loaded impact of methane over a 100-year timescale makes the methane problem look a lot less dire than it truly is.

A boost for biofuels

By counting emissions from burning biofuels as zero, Hochul Math would create incentives to burn “renewable natural gas” from farms and waste, and also to burn wood and other biomass. California has adopted similar rules for its carbon accounting, resulting in a rush to import renewable natural gas refined from biogas into the state.

As a percentage of the state’s emissions, biofuels are pretty small potatoes, no pun intended. There is not nearly enough “renewable natural gas” in the state, or indeed in the country, for New York’s natural gas industry to switch the fuel in its pipelines from fossil methane to methane derived from cow manure and landfill gas. And renewable gas is far more expensive to produce than fossil gas, so it will not help to solve any thorny climate action affordability problems that might arise. But a policy change on biofuel accounting could end up being more devastating to the environment and human health than a shift from 20-year to 100-year methane math, by creating perverse incentives for New York to lay waste to its forests and burn trash in residential neighborhoods.

When the European Union adopted climate targets in 2009, policymakers decided not to count emissions from biofuels. This created an incentive for wood-burning that has led to clear-cutting in the American South: CNN reported in 2021 that more than a hundred acres of North Carolina forest were being mowed down and pelletized to feed into European boilers every day.

The cost of destroying trust

In my view — and you’re welcome to take this with a grain of salt — the Parker/Barrett bill’s most devastating blow would fall on the state’s climate planning process itself. People who have spent years of their lives and careers on the difficult, technical task of drafting collaborative climate policy have spent the past week watching politicians do an end run around their work behind closed doors, and feeling humiliated and betrayed.

“After wasting three years of their time, good luck getting a decent Climate Action Council,” Anshul Gupta of the Climate Reality Project wrote on Twitter. “Only FFs [fossil fuel industry] will volunteer.”

The CAC’s resident greenhouse gas accounting expert, Cornell scientist Robert Howarth, was vocal in his dismay at watching Seggos push for the accounting change. “My friend, I am truly appalled to be hearing this from you at this point in time. Did we not, under your leadership as Climate Action Council co-chair over the past 3 yrs adequately discuss this? WHAT HAS CHANGED,” he tweeted at Seggos.

The state’s greenhouse gas inventory is the foundation on which the Climate Action Council’s scoping plan for decarbonizing the state economy is built. Counting the state’s emissions anew by legislative fiat would undermine every recommendation made in the plan, which was finalized just a few months ago.

For the non-state-agency members of the Climate Action Council — at least the ones whose goal in participating was to develop better climate policy — Hochul’s move to scuttle three years of difficult, technical work was a demoralizing blow.

Community and environmental justice advocates have been especially outraged. Members of the Climate Justice Working Group, who were tasked with the job of coming up with a working definition for “disadvantaged communities” under the climate law, boycotted a Tuesday meeting in protest, leaving the group without enough attendees to take a vote on approving the meeting minutes.

“Our role on the CWJG has been time consuming, emotional, and weighs heavily on our shoulders as we do all we can to show up for climate justice,” the members wrote in a letter to CAC co-chairs Seggos and Harris opposing the Parker/Barrett bill. Their concern is not just about accounting: A bill to amend the climate law on short notice without public input, they write, “does not align with the democratic and collaborative process that is foundational to the CLCPA.”

So what now? 100-year accounting would have lowered the fees for polluters. Will higher polluter fees mean higher costs for New Yorkers?

Short answer: They don’t have to.

Fossil fuel businesses will indeed try to pass every cent of their increased costs on to consumers by hiking fuel prices. But under a cap-and-invest program, whose governing rules will likely be written by the Department of Environmental Conservation and NYSERDA with a public comment process, New York households will also get rebates from the state, funded by the emissions fees paid by polluters.

If the program is designed right — and that’s something the Hochul administration has a lot of control over — the rebates and the increased fuel costs, for most low-to-middle-income households with typical energy use, will cancel each other out. For ultra-high-income households on the upper end of the earnings scale, whose fuel use and carbon emissions tend to dwarf that of the average New Yorker, the rebates might or might not apply. If they do, they won’t be enough to offset the extra costs of high fuel use, and the increased costs will act as an incentive to switch to clean energy. Who pays more out-of-pocket under cap-and-invest, and who breaks even or comes out ahead, depends on how the rules are written.

Lower-income New Yorkers, for whom switching to clean energy or lowering fuel use is almost impossible, will end up benefiting also from the portion of the carbon fees that the state doesn’t spend on rebates. A key goal of Hochul’s cap-and-invest plan is to raise more funds for projects that help lower-income households and communities shift away from fossil fuels, like home weatherization and public EV chargers. It’s unlikely that New York policymakers would abandon that goal, but it would theoretically be possible to create a cap-and-invest plan that returns every cent of the funds raised directly to households as rebates. Even without spending a dime on energy programs, a “revenue-neutral” cap-and-invest plan would still create economywide incentives to shift to clean energy.

Claiming that higher fees for fossil fuel companies will result in more pain for New York households is a little like complaining that your cup of coffee got more expensive because you had to pay with a $100 bill instead of a $10. There’s no reason that a cap-and-invest program based on tougher carbon accounting can’t be written to deliver just as much of a rebate to the typical New York household as one based on looser figures. The more revenue the program takes in from polluters, the more it has available to give back to households.

Because the rules of cap-and-invest haven’t been ironed out yet, even if we could be certain how much the emissions fees would cost, it’s impossible to say exactly what the costs of Hochul’s cap-and-invest plan will be to most New York households, if any. But the scary (and largely unexamined) figures touted by the Hochul administration as potential fossil-fuel cost hikes from cap-and-invest — 63 cents a gallon for gasoline, an almost 80 percent hike in natural gas costs — are only part of the picture, and it’s disingenuous of Hochul to imply that lowering the industry’s emissions fees is the only way to soften the blow to ratepayers and gas-buyers.

Gas pipelines: A cost bomb waiting to go off

There’s another looming fossil fuel problem poised to hit ordinary New Yorkers in the wallet, regardless of whether the state charges carbon fees, and that’s the state’s natural gas infrastructure system. New York’s 50,000 miles of gas pipe are aging, leaking, and expensive to replace. The cost of their perpetual replacement is built into utility rates. As more and more New York households move away from natural gas, some of them driven by increasingly volatile gas prices, those costs are not only rising, but falling on a shrinking number of natural gas customers, as a recent report from the Building Decarbonization Coalition explains.

“Today, ratepayers’ gas bills are increasing and will continue to do so in the coming years, irrespective of the influence of climate policies and building electrification efforts. The primary reason for rising costs is the continuous replacement of old cast iron and unprotected steel pipes that are considered ‘leak-prone,’” the authors write.

Careful planning to downsize New York’s natural gas infrastructure, and state funding to keep the costs of maintaining the system from falling hard on renters and lower-income homeowners who can’t afford to get off gas, is badly needed. But in order for that to happen, the state needs to pass a law that aligns the Public Service Commission with that goal.

A bill that would give the PSC the authority to start planning for gas infrastructure decommissioning, dubbed the NY HEAT Act, is currently on the table in budget negotiations. The bill would also do away with an old policy that requires gas companies to subsidize the cost of hooking up new households within 100 feet of a gas line, a cost that gets passed on to all of the utility’s other gas customers.

If we don’t adopt Hochul Math, what else can New York do to keep cap-and-invest from pushing costs onto regular people?

If the Hochul administration is committed to making sure cap-and-invest doesn’t hit New Yorkers in the wallet, making the rebate to households larger and helping people get their homes and vehicles off fossil fuels aren’t the only options on the table.

The climate plan itself contains language that points to other ways. In the section that talks about cap-and-invest policy, the scoping plan points to ways that the program could act to exercise control of the fees, or “allowances,” paid by polluters themselves:

“Development of a cap-and-invest program would include measures to provide a level of price certainty. Examples include establishing a minimum allowance price and an emission containment reserve under which fewer allowances are made available if prices are below a specified level, similar to the RGGI program. Cap-and-invest programs could also include soft price ceilings to limit costs. RGGI, for example, includes a cost containment reserve mechanism that releases additional allowances at higher price levels.”

RGGI, for those not in the know, is a multi-state cap-and-trade program for the electrical power industry, launched in 2005, that auctions off emissions permits to fossil-fueled power producers and funds energy conservation programs. “Cap-and-invest” would work in a similar manner — except that it would be much larger and more ambitious, and give rebates directly to households.

Cap-and-invest sounds hellaciously complicated!

It is complicated, and it’s very easy to stir up political opposition by scaring people about its impact on energy costs. That’s why some climate advocates are pushing for a less wonky “tax-the-rich” approach to funding state climate action, aimed at New York’s highest earners. It seems vanishingly unlikely that either the Hochul administration or the legislature will have much appetite for that, though.

I’ll leave it at that for now. This is a big, messy, wonky topic, and there’s a lot to digest. Thoughts? More questions? Hit me up, I’ll do my best: empireofdirt@substack.com.