New York already has a climate law. Why does it need more?

On the uphill battle to put teeth—and funding!—in New York State's climate law, the CLCPA.

Let’s be fair: In 2019, New York’s climate bill was a very big deal.

Is it still?

The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act—or CLCPA, since everything in this space has an acronym—set a series of ambitious targets, tied to a ticking clock that runs through 2050. By 2030, the law requires New York’s electrical grid to be run on 70 percent zero-carbon energy sources (up from about half zero-carbon now). By 2040, the grid must be decarbonized. By 2050, the entire $2 trillion state economy must be—with a target of greenhouse gas emissions slashed by 85 percent from 1990 levels. Vox called it “the most ambitious target in the country.”

Three years later, the CLCPA is looking a little long in the tooth. While New York legislators passed the law, and are still patting themselves on the back for it, they have yet to act on funding it. Other states are starting to leapfrog past New York in passing bold targets and putting their climate plans into action.

A lot of New Yorkers are unaware — or maybe only vaguely aware — of the climate law, where it currently stands, and what it does. That’s too bad, but it’s thoroughly predictable. There are a lot of reasons for it:

- Local news has been decimated. In my rural area, many towns don’t even have a local newspaper.

- Climate policymaking is, let’s face it, a pretty deadly process—although if you want to watch the state Climate Action Council’s hours-long meetings online, complete with hundred-slide PowerPoint presentations from NYSERDA system modeling wizards, they’re all archived on YouTube. Who doesn’t thrill to the prospect of “Scoping Plan Feedback Session 2: Economywide Strategies, Electricity, and Climate Justice”?

- The COVID pandemic overwhelmed both public attention and state government energy soon after the law was passed, and then there was the tragicomedy of the Cuomo implosion.

- Climate is a challenging, technical beat, and even where local and state news is a little more robust, most outlets don’t have the resources to assign reporters to it full-time. (As one of just two staffers at The River last year, I sort of assigned myself—with the hearty blessing of the experimental news site’s overlords at Chronogram, and of editor Phillip Pantuso, who’s now my editor at the Times Union’s Hudson Valley section. As a freelancer, now that The River has scaled back even from its modest 2021 ambitions, I’m too stubborn to do something saner with my career.)

Among New Yorkers who are paying attention to the state’s climate plan, which is due to be finalized at the end of 2022, I see two main reactions. There is a line of thinking, especially in rural upstate areas, that sees the CLCPA as an unstoppable juggernaut that will impose new state mandates on local government, and on people’s individual household decisions. Industry groups like the utility-funded New Yorkers for Affordable Energy, along with a bevy of local propane and fuel oil businesses, have tapped into these fears with misleading social media campaigns, mailers, television spending, and general astroturfing in an effort to mobilize public opinion against state climate policy. The conservative think tank Empire Center, who I see as grounded in actual data but very much agenda-driven on this issue, has been banging that drum also.

Among the climate-concerned, it’s the opposite: People worry that the CLCPA is toothless, and that without funding and supportive legislation, the emerging climate plan it has set in motion is nothing but a bunch of empty goals the state will blow past, and a vast time-wasting exercise for government nerds. Pete Sikora, a firebreathing NYC and NYS climate advocate with a well-deserved reputation for not mincing words in sober policy circles, summed up the fear that the climate law won’t be worth the paper it’s printed on in an op-ed for NY Focus this spring. “It won’t be enough to wave multi-hundred page plans by an obscure regulatory body with no enforcement power in front of the legislature and governor’s mansion,” he writes. “No one should pretend the CLCPA will save us.”

Take this with a grain of salt, but from where I sit, these fears are both off base in interesting ways — and a useful corrective in others. And lest that come off as typical insufferable journo-type bothsidesism: I intend to get into the details, where the devil usually is. It’s early days for this newsletter, and I’m still in the process of figuring out what it’s good for, but I hope to expand on that topic in future issues.

It is undeniably true that the state legislature has whiffed for a few years in a row on putting its money where its mouth is on climate. In February, I wrote a story for The River about what state climate advocates were hoping to get done in 2022: a head start on making newly-constructed buildings all-electric, a boost for public power, curbs on the climate-torching practice of buying old power plants to run proof-of-work crypto, legislation to bring the gas-oriented public service law that governs utilities into the renewable era, and, of course, money. The state Climate Action Council and its NYSERDA wizards estimate that putting the CLCPA into action will cost anywhere between $10 and $15 billion a year, an amount that dwarfs the multi-million-dollar climate and energy projects Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office occasionally touts in press releases.

Almost none of that legislation passed, except for the crypto bill — which is still sitting on Gov. Kathy Hochul’s desk. Maybe she’ll sign it.

This year, climate advocates are pushing again for money for the state to take real action on decarbonization, and also on the climate law’s equity provisions, which seek to shunt funding and green jobs into “disadvantaged communities” (a technical term, in climate policy) that have been hit hard by both climate impacts and the illness that comes with concentrated fossil fuel pollution.

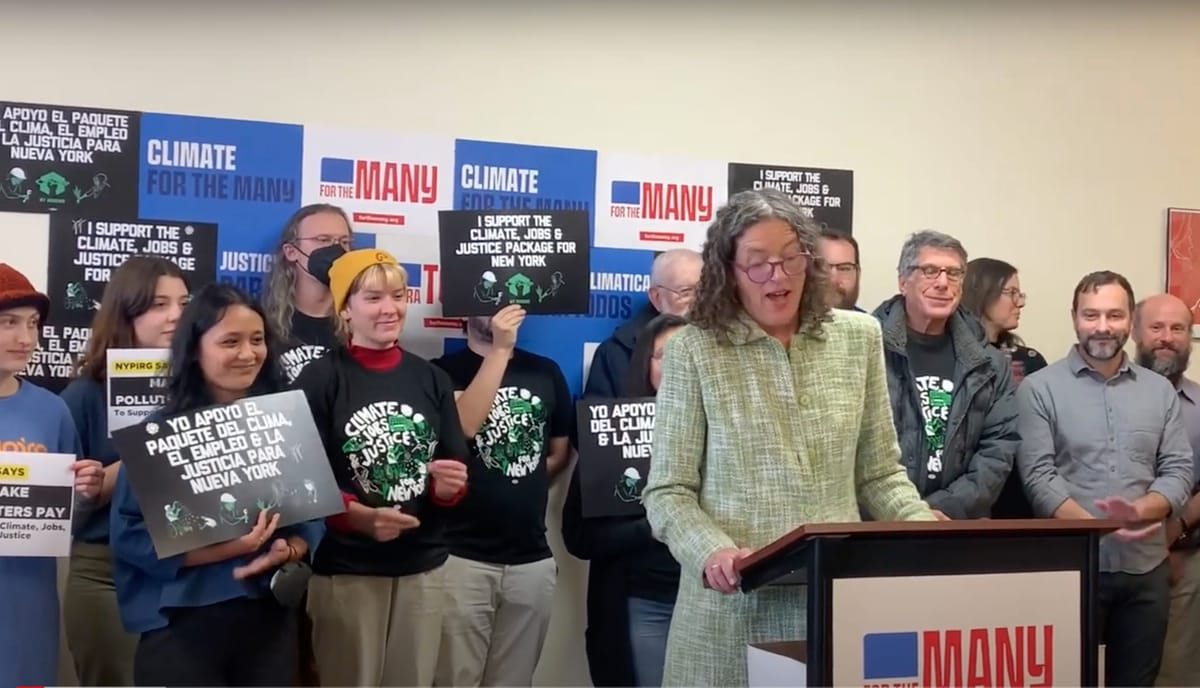

This year, advocates have also gotten more organized about speaking with one voice for climate legislation that goes beyond funding. Last week, NY Renews, a coalition of more than 300 climate, community, labor, and environment organizations, launched a campaign for the “Climate, Jobs & Justice Package,” a suite of legislation aimed at turning the CLCPA into concrete plans with money to carry them out. I don’t doubt there were spicy conversations behind the scenes on what to include in that package. For a coalition as large and unwieldy as NY Renews — whose members run the gamut from genteel old-school environmental groups with deep pockets to scrappy community-based groups focused on racial and neighborhood justice — getting more than a dozen steering committee orgs and 300+ rank-and-file members to agree on a slate of specific plans for the zero-carbon transition is no mean feat.

I wrote about the package for the Times Union on Friday— what’s in it, and also what’s not. (Not to be found in the package NY Renews is pushing for: Legislation that sets a date for electrifying new construction, without which New York won’t hit its climate goals. That’s a whole kettle of fish in its own right, and we’ll get into it in future issues of this newsletter.)

Legislators and local climate leaders spoke at rallies across the state in support of the NY Renews package. I talked to the ones who spoke in Kingston, because that’s who’s local to me: newly-elected Ulster County executive Jen Metzger, a former state senator who helped get the CLCPA passed, and also-newly-elected soon-to-be-Assemblymember Sarahana Shrestha, a socialist who beat incumbent Democrat Kevin Cahill in a stunning primary upset this year, and for whom climate and public power issues are front and center in her effort to reach nonvoters and build support outside of the Hudson Valley Democratic machine.

Give my story a read, if you’ve made it this far. And let me know what you think. I’d love to hear from you.

DEAR READER: I am so heartened by the response to this newsletter. I’ve got almost 300 subscribers and counting, some of you are paying, and hot damn, most of you are actually reading it. Bless. THANK you.

I’d like to thank those of you who have boosted this newsletter on social media too. I’m in my feelings about it. Over at Mastodon, where I’ve put a cautious toe in the water (come find me if you’re there!), energy attorney Justin Gundlach, who works on utility regulatory policy with the Building Decarbonization Coalition, gave me a shoutout I’m still blushing about. “One of a very small number of reporters who look closely at concrete instances — successful and otherwise — of what is often blithely called ‘policy implementation,’” he says. Sir, please, this is an Arby’s.

I have a fair number of Founding Members here who have opted to pay a little extra to get this newsletter off the ground. I’d like to feature them each with a shoutout in a future issue. If you’re a founding member, think about how you’d like to be introduced to the class — or if you’d prefer to remain anonymous, you can let me know if there’s a local org or business you’d like to give a boost to. I’ll be emailing you all soon.

PASS THE HAT: Last Monday, there was a devastating fire at M&M Motors, a longtime local business in Stamford. My department didn’t respond, we’re a little far to be called on for Stamford mutual aid, but more than 100 firefighters from companies in Delaware, Schoharie, and Greene County did. They’re holding a spaghetti dinner fundraiser next week at Mac-A-Doodles for owners Mike Kiel and Marty Cole, but if you want to chip in online, there’s a GoFundMe page.

Please send me all your Catskills-local fundraiser tips, I’ll boost them here. (I’ll vet them for being legit. You know what they say: If your mother says she loves you, check it out.)