New York plans to put a price on carbon. What does that mean?

On the first day of Christmas, NYSERDA gave to me: A cap-and-invest study

Welcome to the Twelve Days of New York Climate Nerd Christmas, an idea I had after too much eggnog.

This holiday season, I’m sending out twelve newsletters, each dedicated to some climate-related present we all got recently here in New York State.

Just like real Christmas presents: Some of them might be just what you wanted this year. Others might be lumps of coal. We’ll open them and find out.

I’ll kick things off with a big one: On December 20, the state Department of Environmental Conservation and NYSERDA jointly released a sneak peek at the state’s planned cap-and-invest program. It’s a set of regulations that, when enacted, will play a key role in nudging the state’s $2 trillion economy off fossil fuels over the next few decades, and in ensuring that the burden of the clean-energy transition doesn’t fall on ordinary New Yorkers.

Of course, it wouldn’t be a state environmental program without an acronym. It’s called NYCI, for “New York Cap and Invest” — and the policy folks are pronouncing it “Nicky,” which seems seasonally appropriate.

What is cap-and-invest?

If “cap-and-invest” sounds a lot like “cap-and-trade,” that’s because it is. The idea is that the state DEC puts an annual limit on the amount of greenhouse gas emissions polluters can make — that’s the “cap,” and it will decrease every year. Large polluters will then have to buy allowances in a NYSERDA auction in order to gain the right to make those emissions.

A third of the money raised will go directly to low- and middle-income New Yorkers in the form of some sort of dividend payment, to help offset any increase in energy prices they will face from the program. The rest will go toward funding for projects that will help New York’s homes and businesses make the transition away from fossil fuels and toward cleaner forms of energy, heat, and transportation. As the twin pressures of the carrot (funding for clean energy) and the stick (payments for the right to pollute) push the transition away from fossil fuels forward, the cap will decline. If it works like it’s supposed to — and that’s a big “if” — New York’s emissions should drop on schedule to meet the ambitious targets laid out in the state’s landmark 2019 climate law, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.

The idea behind cap-and-invest is simple enough, but the devil’s in the details. New York policymakers have a lot of work to do to iron out exactly how the program will work. If they build it wrong, there’s a lot of potential for unintended consequences, whether that’s low-income people having to spend more on energy or economic activity flowing outside of New York State because of perverse incentives.

NYSERDA and the DEC are actively seeking comments on the pre-proposal, and on an affordability study they also released that gets into detail on how best to deliver the program’s cash climate dividends to New York State residents. They are also hosting a series of public web meetings in January about the program:

- Jan. 23, 3 to 4:30 p.m. – The Role of Cap-and-Invest

- Jan. 25, 1 to 4 p.m. – Pre-Proposal Outline Overview

- Jan. 26, 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. – Preliminary Analysis Overview

All of this material lives on the state’s new Cap-and-Invest website, where New Yorkers can also submit public comments about the proposal.

In a way, the forthcoming cap-and-invest plan is already in motion: It’s a direct outgrowth of the 2019 climate law and its scoping plan, which commits the state to taking concrete action to decarbonize the economy and to ensure a just transition for vulnerable New Yorkers. But now, as the CLCPA’s targets become action, the rubber is meeting the road, and there will be a lot of pushback. “Nicky” is likely to stir up fierce political opposition, much like the state’s first steps toward making newly constructed buildings fossil-fuel-free did this spring.

When will it happen?

According to the pre-proposal, the aim is to begin the program in 2025. New York is racing the clock: The 2019 climate law calls for a 40 percent economywide reduction in emissions from 1990 levels by 2030, and some of the recommendations made in the state plan that lays out the roadmap to get there have already been delayed.

What industries will have to buy allowances?

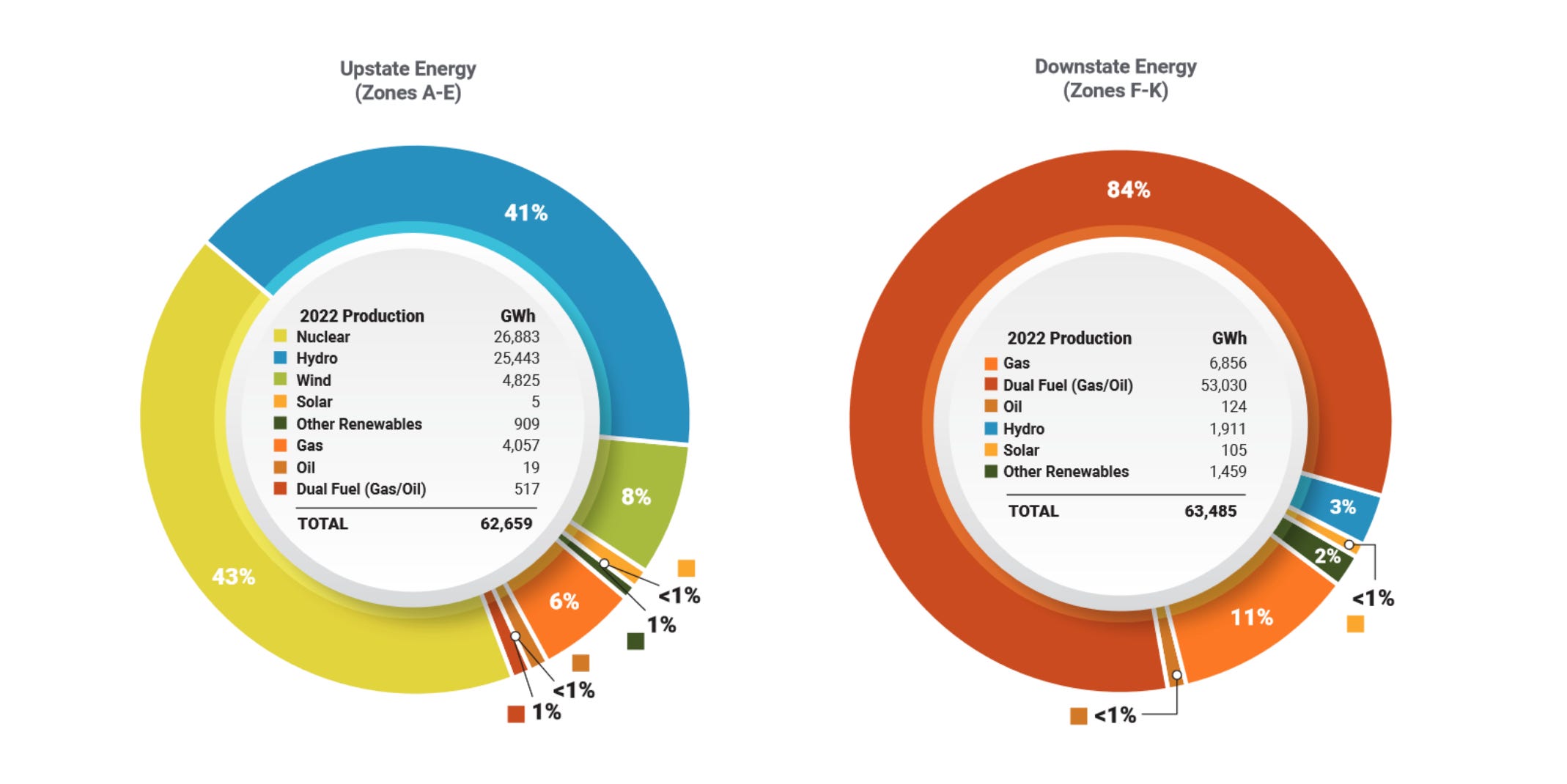

One of the biggest questions that hasn’t yet been answered about the cap-and-invest plan is whether it will apply to fossil-fueled electrical power plants.

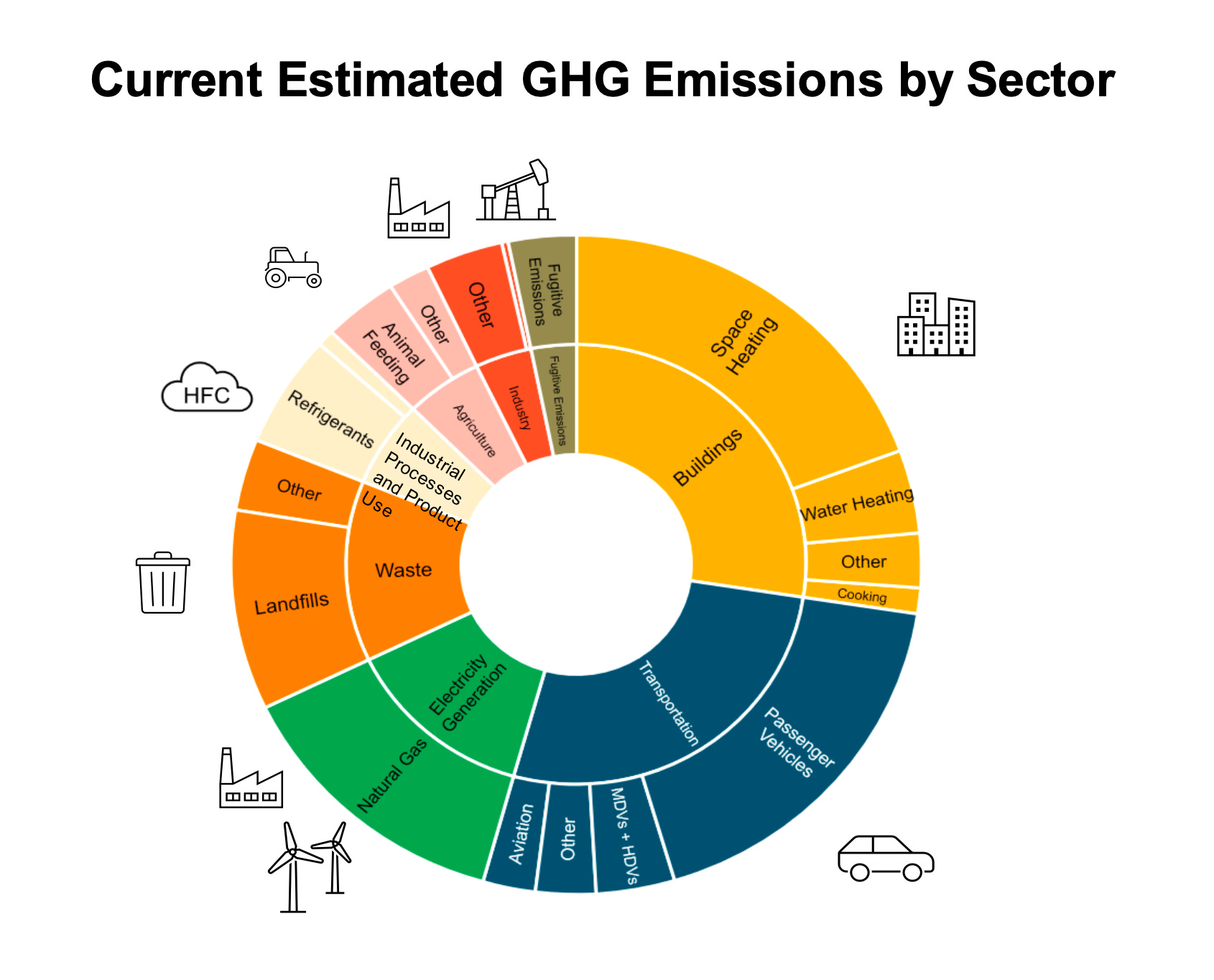

The power sector isn’t the biggest source of New York’s climate pollution. That dubious honor belongs to the state’s aging building stock, with transportation coming in a close second. But power is a pretty large slice of the state’s greenhouse gas pie: about 13 percent in 2019, almost all of it from natural gas that generates the lion’s share of electricity in the New York City area.

So why would New York leave it out of cap-and-invest? Well, for one thing, New York already has a cap-and-trade program for power producers: the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI (pronounced “Reggie”). The state is calling for comments on whether RGGI, cap-and-invest, or some combination of both should be used as the main way to ensure that the power sector meets climate targets.

Another reason why New York might want to slow its roll on folding electricity into cap-and-invest: Anything that increases consumer electricity costs might hold back state progress on climate goals, no matter how that power is produced.

In order to meet its ambitious climate goals over the next few decades, New York has to pull off two feats at once: expanding and cleaning up its fossil-heavy electrical grid especially downstate, and shifting millions of buildings and vehicles that now run on fossil fuels toward electricity. Since heat pumps and EVs tend to make far more efficient use of power than the combustion technology they replace, “electrifying everything” would result in lower overall emissions even if the grid stayed dirty. But in order for electrification of buildings and vehicles to happen, it needs to be affordable for consumers to make the switch — and anything that increases electricity rates has the potential to hold that transition back.

So: Power plants are a maybe for cap-and-invest. What does that leave?

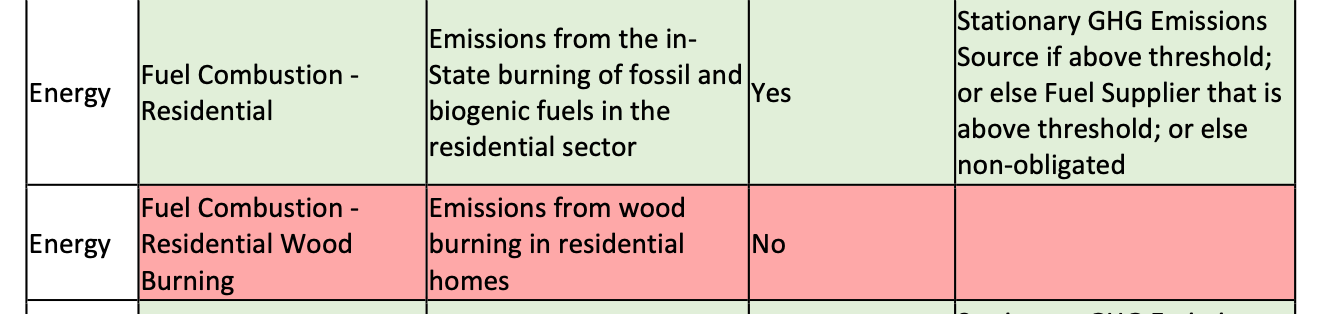

-Fuel. Large fuel suppliers will have to buy allowances for all of the fuel they import into the state, with one big exception: Whatever they sell to the state’s largest polluters.

-Big polluters. If a facility spews emissions that add up to more than 10,000 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, they’ll have to report their emissions to the state. If they go over 25,000 tons, they will need to buy allowances in the cap-and-invest auctions, and their fuel supplier will not have to buy allowances for the fuel they use. To put this in perspective: A home in New York heated with gas or delivered fuel might produce about five to 10 tons of emissions every year.

-Manufacturing, heavy industry, and production of metals and cement.

-Methane from landfills and wastewater treatment plants.

-Leaks from natural gas distribution infrastructure in-state — which, by the way, are also mostly methane. Upstream leaks from wells aren’t covered, although the federal government is already taking aim at cleaning up methane leakage on that end.

A note on methane: It’s the main ingredient in natural gas, and in its unburned form, it is a much more potent short-term driver of climate change than carbon dioxide is. Over the course of decades, methane decays and becomes less potent. New York uses a more rigorous method of counting methane than the federal government and most states. Last spring, the Hochul administrated floated the idea of changing that accounting for the cap-and-invest program — sparking swift and immediate backlash from New York climate world.

So far, it seems that the cap-and-invest program will keep New York’s tougher methane accounting in place.

What’s not covered?

-Livestock. Agriculture is responsible for about six percent of New York’s emissions, much of that from methane (yes, cow burps are contributing to climate change). But it’s hard to measure, and there are undoubtedly more productive (and less politically explosive) ways to deal with agricultural emissions than charging farmers cow burp fees.

-Woodstoves. No, Kathy Hochul is not coming for your woodstove, despite what you may have heard from upstate doomsayers on Facebook. (I got one right here for power outages, and Basil Seggos has assured me personally he’s not going to try to pry it from my cold dead hands. —Ed.)

-Aviation. Airplane fuel is outside of New York’s regulatory jurisdiction, so we won’t be seeing a state carbon fee for jet-setting anytime soon.

-Refrigerants. According to the pre-proposal, regulators are thinking about putting emissions from commercial-scale refrigeration systems into the cap-and-invest program, but are leaving out most refrigerant uses. Some of the refrigerants commonly used in household appliances — including climate-friendly heat pumps — have large greenhouse gas impacts if spilled.

-Methane from individual septic systems. Seriously, how would they even begin to measure it? The mind boggles.

The pre-proposal includes a handy color-coded chart of what’s covered and what’s not, with a few “TBD” entries for areas that need, as state policy wonks like to put it, stakeholder input.

Are offsets allowed?

No.

Some cap-and-trade programs allow polluters to buy offsets, investing in greenhosue gas reduction or sequestration elsewhere to “earn” the right to pollute more locally. New York’s won’t. One of the main reasons is to protect vulnerable communities in the state that already have large sources of pollution nearby.

Greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide and methane, aren’t directly harmful to human health in the same way that particulate pollution is. But the two go together: Wherever fuels are burned, particulates and other pollutants are released along with greenhouse gas pollution, and they have a direct impact on increased mortality and disease in local communities.

Allowing offsets would let a polluter in a “disadvantaged community” — another climate policy term that has an acronym, DAC — keep polluting at high levels locally in ways that impact human health, not just climate. New York’s program seeks to prevent that.

Not allowing offsets is good news for communities like Peekskill — a DAC in Westchester County that is home to the Wheelabrator, a large trash incinerator and the county’s biggest single source of air pollution. In 2022, when NYSERDA and the DEC were holding hearings on the state’s scoping plan across the state, many of the community members who showed up to comment at a hearing in Peekskill talked about how the Wheelabrator’s pollution was hurting the community.

What will this do to energy prices?

Hard to say, since the pre-proposal doesn’t yet have dollar figures on how much New York aims to charge per ton of emissions for pollution allowances in the early stages.

I think it’s fair to say that the policymakers who live and breathe this stuff at the state level are aiming to keep impacts on fuel prices fairly low and gradual, and to return enough of the money raised directly to New Yorkers’ pockets that for low-and-middle-income earners the higher costs and the dividend checks roughly balance out. Since higher-income people tend to use more energy and produce more emissions, and will thus shoulder more of the increased costs of rising fuel prices, it’s possible the costs and dividends from the program will balance out for people at lower levels of income, even though only a third of the funding raised is dedicated to climate dividends.

It’s a difficult balancing act, and it will undoubtedly be the topic of a lot of wrangling and analysis before the final regulations are issued.

If the Hochul administration screws it up badly, there will be intense political fallout. See also: Washington state, where a cap-and-trade program that accidentally jacked up the price of gas too fast is now facing a precarious future as a result.

Right now, in addition to enjoying various subsidies from state and federal governments, the burning of fossil fuel imposes steep costs on society that are paid not only by those who burn it, but by everyone. Those costs tend to fall hardest on the most vulnerable, who also tend to be those with the least power to choose where their energy is coming from or how much they spend on it.

Cap-and-invest, for all its wonkiness and the fact that it’s an easy political target, is an effort to correct that balance. We’ll see if it works.

What happens to the money?

A third of it will be set aside for direct payments to low- and middle-income New Yorkers. A NYSERDA study issued last week alongside the pre-proposal discusses ways that the state can try to ensure that those payments aren’t taxable, that they flow even to households whose income is low enough that they don’t pay income tax, that they don’t interfere with people’s eligibility for state assistance, and that New Yorkers living in areas with higher energy costs get more.

That last bit is relevant to us ruralites. NYSERDA’s study suggests that in adjusting household climate dividend payments by region, the state should take into account both longer driving distances in rural areas and colder temperatures that drive up heating costs.

Two-thirds of the funding raised by auctioning allowances will go into a Climate Investment Account that will fund various projects to accelerate the clean energy transition. Some of those might be aimed at helping individual households and residential neighborhoods electrify as well as larger polluters and industry.

Merry Christmas, Empire of Dirt. Eleven more days left — and I’m pretty sure I know what presents you’re getting, but if you have ideas, feel free to hit me up.

REMINDER: Like I said in my last installment, this newsletter is moving soon. Probably to Ghost, where I’ve set up an account and am working on porting things over. I hope the transition will be pretty seamless for all of you. Stay tuned.